Contract Working Conditions in Tech: What’s It Really Like?

This article is the first in our series on the Contract Worker Disparity Project. Over the next few months, we’ll be sharing our insights and learnings from first-person interviews with contract workers and our industry-wide contract worker survey. To learn more about the project, check out our announcement article.

In this article, we’re examining the conditions for contract workers and the three main themes we’re seeing across the board: disjointed management structure, the precarious nature of contract work, and the firewall between contract workers and direct employees.

Defining Tech’s Shadow Workforce

The workers highlighted in the Contract Worker Disparity Project are often referred to as contingent workers, contractors, or sometimes in large companies—like Google—they get their own nickname (“TVCs” or temps, vendors, and contractors). The many terms used to describe these workers reflect the murkiness and lack of standardization surrounding this part of the labor force.

Contract workers are often indistinguishable from directly-employed workers. In contrast to the contracted service workers who run campus cafeterias or operate transportation shuttles—and work primarily with other contract workers all employed by the same contracting agency—many tech contract workers work in office settings that include integrated teams of direct employees and contract workers. The distinctions between contract workers and direct employees in these settings are insidious and often invisible. Contract workers may do similar job functions to their directly-employed counterparts, but earn lower wages, have fewer benefits, and have little to no control over their working conditions.

Through one agreement type or another, the tech industry is powered by an unseen, underpaid, and under-protected workforce.

Efforts to map the boundaries of the tech contract workforce (and to close the disparity between direct employees and contract workers) are complicated by the scale of the phenomenon. It is widely reported that Google employs more contract workers than direct employees, and early research indicates that other tech companies are not far behind.

Our research found evidence that some companies may start to morph their contracting practices even further in ways that continue to disempower workers—reclassifying contract workers as freelancers. They will end workers’ contracts, then after a period of time offer them their old jobs. This time, however, they are classified as freelancers and sign an agreement with yet another contracting agency, one additional layer removed from the tech company, that takes a higher percentage of each paycheck. The many variations and mutations of contracting practices make it difficult to definitively survey the scale of contracting in tech—or even which workers are contractors. Through one agreement type or another, the tech industry is powered by an unseen, underpaid, and under-protected workforce.

What Does Labor Law Say?

The main law that governs whether someone is an employee (and has access to employee rights like minimum wage, worker’s compensation, equal employment opportunity act, and so on) is called the Fair Labor Standards Act (commonly known as FLSA).

The Fair Labor Standards Act says that you can be employed in one of two ways:

- As an employee of the company

- As an independent contractor who may work with one or more companies

To be classified as an independent contractor, the Department of Labor says there is no single standard or rule, but that there are a series of factors that the courts have taken into consideration. If a worker meets these areas’ qualifications, they may be a direct employee under labor definitions who is misclassified as an independent contractor.

Misclassification creates potential liabilities for companies that can be costly, not to mention its harm to the workers themselves.

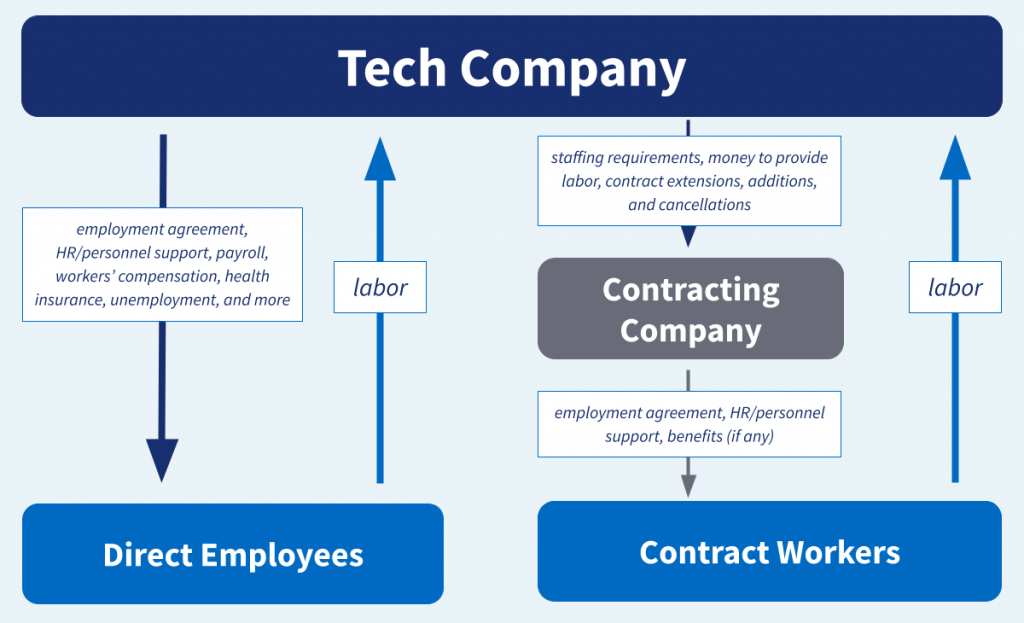

To avoid the liabilities associated with misclassification, many companies have used third-party staffing agencies or vendors to employ contract workers. These arrangements set in motion another potential liability that many companies would like to avoid, called the Joint Employer Standard.

What is the Joint Employer Standard? When two or more businesses co-determine or share control over a worker’s terms of employment (such as pay, schedules, and job duties), then both businesses may be considered to be employers of that worker, or “joint employers.” Consider a common employment arrangement in which a staffing agency hires a worker and assigns her to work at another firm. The staffing agency determines some of the worker’s terms of employment (hiring, wage rate), but the other firm directs her daily tasks and sets her schedule and hours. Because both entities co-determine and share control over the terms and conditions of her employment, both businesses may be found to be joint employers. Joint employers are responsible, both individually and jointly, to employees for compliance with worker protection laws. (EPI, 2017)

Tech companies try to avoid the Joint Employer Standard by artificially separating contract workers from direct employees, as outlined below.

Characteristics of Contract Work

Across the categories of contract work—we see repeated themes that result in a shift of economic risk from large tech companies onto individual workers and their families.

Workers’ experiences are determined in large part by which entity (the contracting agency or the tech company) provides performance evaluation, job extension decisions, human resources support, and payroll services—and whether the two work together to provide the resources and support necessary for the contract worker to fulfill their role.

The workers with whom we spoke report various titles or classifications—temporary worker, full-time temporary worker, contractor, contingent worker—but across the status distinctions, a few themes typified the experience: disjointed management structures, lack of job stability and protections, and an elusive opportunity to transition to full-time direct employment.

Disjointed management structure

Contract workers have two official management relationships: with their contracting agency and with their company supervisors. The contracting agency frequently covers performance feedback (provided from the tech company to the contracting agency, then to the contract worker), time off requests, payroll, and HR functions. The tech manager, most often a direct employee of the tech company, oversees their day-to-day work and determines whether their contracts are extended.

The dual management structure is designed to minimize the tech company’s liability; the more direct the relationship is between a contract worker and a tech company, the more at risk the company is of being legally indistinguishable from a direct employer. That was the argument of the long-serving “temporary” Microsoft contract workers who sued the company in 1996 for the amount they would have earned if classified as direct employees. The workers argued, in part, that performing the same job functions and working for the same managers as direct employees entitled them to the same benefits. Microsoft settled the lawsuit in 2000, and the case has informed how companies walk the tightrope between contract and direct employees ever since.

In practice, reporting to two entities leaves workers without the support they need to perform their roles. Many actors working together from separate offices requires timely and coordinated communication to pull off, as well as regular training for tech managers to understand how to supervise hybrid teams of direct and contract workers. Many of the workers we interviewed detailed that they reported to a series of tech managers during their contracts, with many stepping into the role with seemingly minimal knowledge on the unique legal and company rules that applied to their direct reports. As such, there are inconsistent practices in how well the tech managers and the hiring agencies work together to employ the contract workers.

It becomes the contract workers’ obligation to piece together expectations from the tech company and contracting agency when they fail to collaborate. One worker shared that early during the coronavirus pandemic, they and their fellow contract workers hadn’t received information on how their benefits, including their right to sick leave, had changed with new federal and state laws. They tracked down the appropriate legal information and shared it with their fellow contract workers. When their managers found out, they were scolded. They were told that the information needed to come from each workers’ contracting agency directly, even though weeks had already gone by without employers disclosing the news of their legal rights to the contract workers. Critical information gets lost in a dual reporting structure, leaving workers to use valuable time tracking down the appropriate authority—and to be reprimanded for not obeying the often invisible lines of who is responsible for what.

Ambiguous jobs aren’t uncommon even for direct employees. For Louisa, however, this haziness threatened her livelihood.

Louisa* accepted a position working on public policy at a major tech company. She learned quickly, however, that the duties her contracting agency brought her on to fulfill actually conflicted with the tech company’s internal rules precluding her from certain activities critical to her job, such as speaking on behalf of the company and managing relationships with external partners. Despite numerous requests to her tech manager to clarify on how she should navigate the company’s internal rules and still fulfill her role, Louisa received no guidance. She was assigned ad hoc tasks, but was never given a clear metric for how she could meet or exceed expectations. She sensed that her first manager didn’t understand how to apply the company’s contractor policies well enough to revise Louisa’s job scope.

Adding to her difficulties, that manager was later replaced with someone who had even less information on Louisa’s role. Louisa then had to rebuild the relationship with the person who could extend her contracts and help her convert to direct employment—without a clear sense of what management needed from her in the first place.

Ambiguous jobs aren’t uncommon even for direct employees. For Louisa, however, this haziness threatened her livelihood; contracts are often extended just a few months at a time and can end immediately without notice. By workers’ own characterizations, their experiences and satisfaction as contract workers are determined by the daily precarity of their jobs.

The Precarious Nature of Contract Work

Contract workers sign an initial contract, frequently for a six-month term, and then have their jobs extended in repeated, smaller increments. Employers tout the flexibility that this affords the workers. Afterall, they are also not beholden to the company for more than a few months at a time. They argue that contract workers can pick up a contract to see them through brief periods of what would otherwise be unemployment.

In speaking with the workers themselves, TechEquity found few that thought of it as a temporary role. Most express an understanding of the temporal bounds of their contracts, but with a hope that they would continue receiving extensions until they were eventually converted into direct employees.

The contract practices embed instability into the job. Tech managers are empowered to end contracts at any time, for any reason, whether it be disappointing performance or personal bias. This heightens the existing power differential between workers and supervisors by compelling contract workers’ acceptance of poor working conditions and treatment in order to preserve the income supporting their families.

Workers report being told that their contracts were extended only after the fact, depriving them of the chance to discuss wage increases or better benefits. Because their supervisors retain all power to extend or cancel their contracts, speaking up about workplace issues can mean risking one’s economic security and opportunities for future employment.

One worker confirmed that when workplace issues arise, they wouldn’t go through the established reporting structures because they had seen too few concerns meaningfully addressed that way, but it might serve to anger their supervisor who would then fire them or fail to renew their contract.

Understanding how departments budget for labor reveals that there are also systemic factors causing contractor instability. Department managers have two personnel options: direct employees and contract workers. Each one is a separate line item in the budget, with the contractor budget growing comparatively faster than that of the direct employees. To hedge against annual budget changes, department heads have opted to use contract workers on repeated (or not) short contracts; the short terms give them flexibility to constantly balance their budget by getting rid of contract workers reaching the end of their term.

The corporate financial uncertainty is shifted to the least protected workers, contract workers whose job security is the first at risk anytime departments need to reconcile their finances, or businesses want to “evolve.” Early in the COVID-19 crisis, Tesla announced that it was cutting hundreds of contract workers from its car and battery factories due to pandemic-related closures. That same year, Tesla shareholders saw their investments increase 700%. After acquiring Nokia, Microsoft similarly announced that its current and future contract workers would be subject to 18-month term restrictions. It’s unclear how many of the company’s 80,000 contract workers were immediately affected by the new policy.

Because their supervisors retain all power to extend or cancel their contracts, speaking up about workplace issues can mean risking one’s economic security and opportunities for future employment.

Given these budget practices, conversion to direct employment—the hope for many contract workers when they accept their positions— is rare. Of the workers TechEquity has spoken to, only one had been approached by their supervisors about converting to work for the tech company directly. That worker declined, having already accepted a direct employment position that paid less but offered benefits and an opportunity to be a part of a team that valued their unique contributions. For the others, vague commitments and promises of future conversions are all that ever came of their hopes of direct employment at tech companies.

The growing class of workers across tech and other industries who face precarious, under-, and irregular employment is sometimes called “the precariat,” a term coined by economist Guy Standing to demarcate the emergence of employment volatility as the norm for many workers.

Firewall Between Contract Workers and Direct Employees

The practices that companies use to keep contract workers legally distinct (and shield themselves from the legal responsibilities of direct employment) promote the two-tiered worker hierarchy frequently called tech’s caste system. The separation of workers affects everything from badge color, shuttle service, and company-wide meeting privileges to contract workers’ access to internal intranet systems and even certain team meetings.

In addition to creating business inefficiencies, segregating necessary job resources encourages a cultural hierarchy amongst colleagues. Many workers reported that power differentials between workers caused friction that ultimately impeded their ability to complete their work. Dat*, for example, was excited to make a career pivot into working for a tech start up, having always wanted to be a part of a small team of ambitious but down-to-earth colleagues. What they found, however, was a new version of the old boys club.

“It was always so uncomfortable. I always felt like there was such a divide. I thought that, ‘oh well eventually they’re going to hire me on permanently, or eventually the team is going to warm up to me.’ But no, I always felt like an outsider.”

Dat*

The final straw came when Dat was prevented from attending the company’s remote retreat—which Dat had planned. Not only did they miss out on the four-figure bonus that everyone else received, they missed out on a formative bonding experience with their colleagues. “At that point I was just like, ‘oh, I will never be a part of this team. Like ever.’” Dat’s company ended their contract less than a year later. A former colleague later shared with Dat that their contract was ended because the team didn’t feel like they “clicked.”

Contract workers are also excluded from opportunities to inform workplace conditions and culture in more general settings, in which they could advise their companies on key blindspots. Last summer, when workers across the country started having conversations about how structural inequality and white supremacy are perpetuated in the workplace, contract workers were largely prohibited from participating. TechEquity’s early research indicates that tech contract workers might be a more diverse set of workers than direct employees. When this possibility is considered with their exclusion from team-building activities—including retreats, all hands meetings, and operations meetings—the practices that maximize tech profit and minimize tech liability could also entrench tech’s discriminatory reputation.

So, What?

As many in the technology space will tell you—speed, efficiency, and innovation matter. Often, this is how the move to expand the contract workforce is justified. These arrangements allow a company to quickly scale up a specific type of expertise or fill an immediate need. In practice, however, these arrangements are often wide-reaching, long-lasting, and inherently exploitative if they are not managed well. The move to a large, contract workforce allows for companies to absolve themselves of legal responsibility to the workers they rely on to make their companies run—both in terms of ongoing employment, wage rates, and benefits, but also in terms of protecting them from sexual harassment, racial discrimination, and ensuring healthy overall working conditions.

The contracting phenomenon is comprised of relationships that rely on intensified power imbalances: between the worker and the contracting agency, between the worker and their supervisors, between the worker and their directly-employed colleagues, and ultimately, between the worker and the tech giants.

Each relationship fissures power away from the worker to, ultimately, business interests. The result is that large, multi-billion dollar companies are shifting economic risk from their legally-protected corporation to individual workers and their families. Leaving workers silent, fearful, and frankly angry that one wrong question, one awkward conversation, one team member not feeling like “they are a fit” could result in them being out of work and losing the long-sought opportunity to join the “true” tech workforce as a direct employee.

The push to maximize profits by shifting to contract workers explains why the practice is so prevalent, in the tech industry and many others. The scale combined with poor working conditions would seem ripe for worker organizing and advocacy. In one high-profile effort, Google contract workers organized for better treatment with direct employees and ultimately pressured the company to issue minimum contract standards for its contract workers.

The result is that large, multi-billion dollar companies are shifting economic risk from their legally-protected corporation to individual workers and their families.

Despite efforts like those at Google, workers across companies that TechEquity has spoken with still expressed fear of losing their jobs if they raised concerns about poor treatment. Their fears seem validated by stories like that of the Google contract worker who was fired last year (after the minimum contracting standards were put in place) after questioning why she couldn’t discuss wages with other workers.

But for every contract worker disillusioned by their experiences, there are more people returning to the workforce from school or parenting, making a career pivot, or otherwise struggling to find work in the post-COVID economy who see contracting as a stepping stone.

This power imbalance, and the very real ramifications it has for the well-being of workers and their families, requires attention. Accounting for successful yet isolated organizing efforts, there is still work to do to eliminate tech’s caste system and ensure that the industry’s reputation for creating economic prosperity applies to the communities they operate within, and to the least protected workers on which their business models depend. The workers highlighted in the Contract Worker Disparity Project point to the precarious nature of contracting and the dysfunctional relationships between all involved—contract worker, tech manager, contracting agency, and direct employees—as key reasons their contracting experiences have been so poor, and critical levers to pull for meaningful progress across the contract workforce.

*Identifying characteristics have been changed to protect participants’ anonymity.