Separate and Unequal: How Tech’s Reliance on Disproportionately Diverse, Segregated, and Underpaid Contract Workers Exacerbates Inequality

The Contract Worker Disparity Project is a first-of-its-kind worker-centered research initiative combining workers’ first-hand accounts, industry research, and a sector-wide sampling to reveal contract work practices in the tech industry. Previous reports for the initiative investigated the working conditions of contract workers, the role and business models of hiring agencies in the phenomenon, and whether the practice is a stepping stone for workers or the latest method to hollow out the middle class. This paper, issued jointly by Project Include and TechEquity Collaborative, looks at the worker, company, consumer, and societal impacts of wage and demographic disparities in tech contract work.

Introduction

Spurred by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd by police, U.S. employers pledged to “do better”—making commitments to advance racial justice within their companies and their communities. Tech was no exception. Companies promised to work with more Black-owned vendors, modernize their recruiting and hiring practices, serve more people with their products, build more equitable pathways into their companies, and more.

These commitments are necessary, long overdue, and have the potential to create meaningful change for some. Lost from the analysis of these commitments, however, is an investigation of the workers left behind: contract workers and tech’s vast contingent workforce whose employment status keeps them from accessing the benefits provided to directly-employed workers.

New data from Project Include and TechEquity Collaborative underscores that Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Asian, women, and nonbinary people are overrepresented as contract workers compared to the directly-employed tech workforce. The data further complicates the picture of tech companies’ commitments to becoming anti-racist employers. It suggests that tech’s new civic ethos—spurred by the violence Black people experience at the hands of state actors—fails to benefit tech’s disproportionately diverse groups of workers.

Lack of Diversity in Tech Persists—Unless You Consider Contract Workers

One of the trusted sources for demographic analysis of the tech industry is a 2014 report from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. That report analyzed EEO-1 reports’ roughly one hundred data points on race, gender, and classification submitted annually about employees. Aggregated data is made available to the public each year, but the 2014 report analyzed the longform data submissions from all tech employers. While the public EEO-1 reports fail to disaggregate data in the “two or more races” category or collect gender data beyond “male” and “female”, the EEOC analysis provides a relatively comprehensive yardstick against which to measure later progress. [Note: Category labels provided by the EEOC do not reflect our preferred language for gender and racialized categories]

The analysis found most racial and gender disparities in tech were more severe than other private sector industries (EEOC labels are reflected): white workers were 68.5% of total employment compared to 63.5% in other industries, Asian American workers were 14% compared 5.8%, Black workers were 7.4% compared to 14.4%, Latinx workers 8% while 13.9% overall, and men were 64% compared to 52%, women 36% though 48% of other private-industry employment.

Notably, it found gender and racial disparities were worse for tech workers in Silicon Valley than those employed in the region’s other sectors. Such deviations from the norm were not attributable to local demographic distinctions; the discriminatory hiring practices were unique to the industry.

The racial disparities persisted in earnings, too. The report states, “Based on data from the American Community Survey, there is a racial and ethnic pay gap as well: Asian Americans reported the highest average earnings in STEM occupations, while non-Hispanic whites also had above average earnings; Black and Hispanic professionals earned below average wages in 2012.” The report notably does not analyze data on Native American, Native Hawaiian, or Indigenous wage disparities, for which public data is extremely limited. Nor does it disaggregate Asian American wage information to investigate disparities within and between AAPI ethnicities, each with unique histories of xenophobia, colonialism, and economic oppression that affect present day workforce outcomes. The 2016 report, “Tech’s Invisible Workforce,” found that while Indian Americans in tech earned an average of $115,000, Vietnamese and Filipino workers earned less than half that amount. Despite the oversights of the EEOC findings, the report provides a useful baseline for analysis, if an unsurprising one to advocates who had been raising a flag about racial bias in the tech workforce for years.

More recent reports and updates on tech diversity are all tasked with finding new ways of saying that the 2014 disparities persist. There has indeed been much ink spilled over the prototypical tech worker: most likely a young, white man, with the prerequisite degrees from one of a small handful of orthodox institutions and connected to the industry through a vast network of personal and academic connections who lit the path to his $146,000/year desk job.

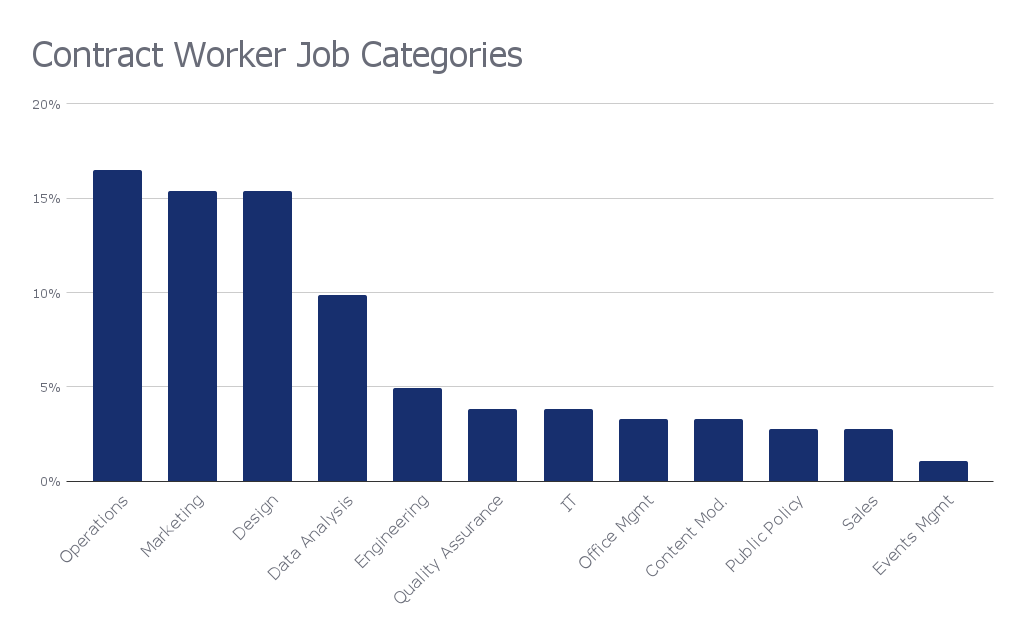

This common perception—perhaps a useful control variable for understanding some of the industry’s inequities— overgeneralizes the characteristics of tech’s emergent workforce. Contract workers, like the prototypical worker, disproportionately hold four-year and advanced degrees but most other commonalities end there, according to new data from Project Include and TechEquity Collaborative.

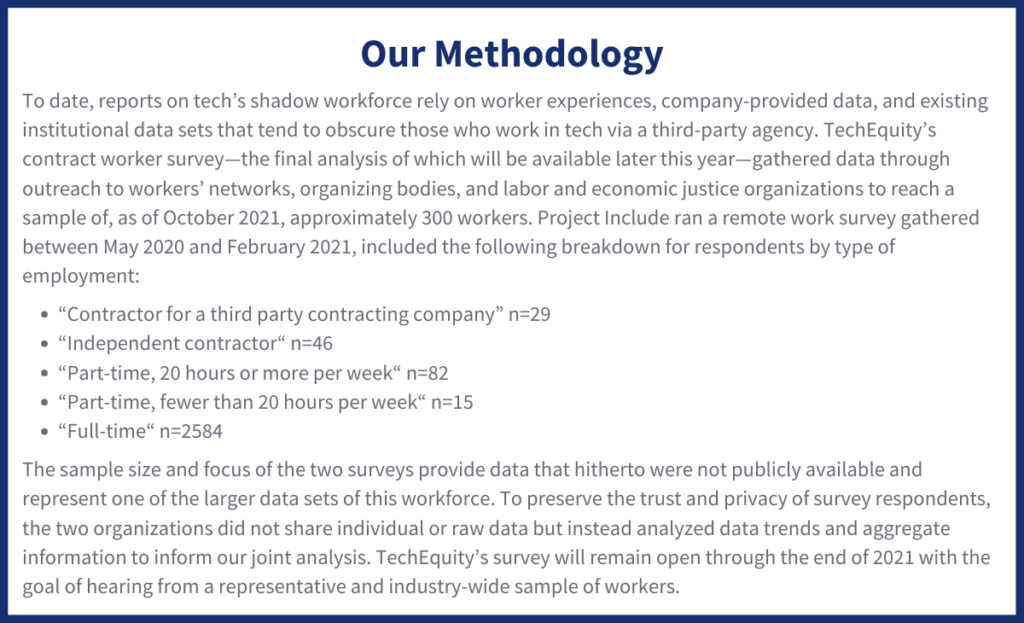

The Project Include analysis of tech workers’ experiences of harm during the pandemic combined with initial data from TechEquity’s ongoing contract worker survey indicate that the demographic trends of the contingent workforce at tech companies—those who are hired through and employed by third-party entities, often on tenuous contracts—are the reverse of the directly-employed workforce: Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian workers, women, and nonbinary workers are over-represented in this class. Over half of the workers identify as members of racialized groups: 9.8% Black, 17.5% Hispanic or Latinx, 18.25% Asian or Asian American, 2% Native American, 0.72% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 4% another race, and 57.6% white (the sum greater than 100% reflects respondents’ ability to select all categories that applied to them).

Contract workers were also more likely to be women and nonbinary or gender-expansive than direct tech workers. Sixty percent of survey respondents were women and 5.8% nonbinary, genderqueer, or gender fluid; 32% were men. Reliable data on the number and rates of gender-expansive people in America are still emerging, with one recent study finding there to be 1.2 million nonbinary people, or 0.004% of the total U.S. population, while other data indicate that 5% of startup workers are nonbinary—though this doesn’t incorporate the employees who chose not to answer to protect their privacy.

For every single non-white racialized category, the rate of employment in contract work was greater than the rate of employment of those same racialized groups in directly employed roles at the tech company. In short, contract workers are the closest thing tech has to a representative workforce.

Disparities in Pay Exacerbate Inequity

Full-time employment opportunities are not the only area where workers of color, women, and nonbinary people experience inequity. Preliminary data and contract workers’ descriptions of their job functions support workers’ assertions that they perform similar work as direct employees—for a fraction of the pay.

Of the preliminary software development contract worker survey respondents who disclosed salary information, just 25% reported earning $86,000 a year or more, putting 75% of those contract workers in the lowest-paid 25th percentile of software developers according to 2019 analysis by U.S. News and World Reports.

To the extent that tech has diversified since 2014, it has done so by keeping its direct employee statistics in stasis while disproportionately hiring people of color, women and nonbinary workers into lower-paying, more precarious contract roles.

According to survey data, data analysts under contract frequently reported earning between $30-75 an hour, putting them in the middle of average earnings for the field. The contract worker wages, however, do not include the cost of healthcare, unpaid time off, retirement contributions, or other fringe benefits that augment direct employee salaries above take-home pay.

Notable, too, is the wide variance in what contract workers earn even compared to other contract workers. Survey respondents are evenly distributed between $15 and $75 hourly wages, a distribution that encompasses several income brackets and degrees of financial stability. While additional analysis is needed to understand the experiences of workers in different positions within the contract work phenomenon, TechEquity’s analysis of contract workers is intentionally broad. The contract workers themselves indicate that it is a variety of factors, not just wages or earnings, that make the role precarious—including short employment timelines, the opacity of the staffing agency business model, the ambiguity surrounding contract renewal and raises, and more.

To the extent that tech has diversified since 2014, it has done so by keeping its direct employee statistics in stasis while disproportionately hiring people of color, women and nonbinary workers into lower-paying, more precarious contract roles.

Increasing Harm for Increasingly Diverse Contract Workforce

Traditionally, research reports are quick to point out quantitative reference points to demonstrate disparities in experience; however, there is a qualitative impact in upholding these inequities. Contract workers often report having less protection in navigating workplace harms. Our research shows less than a third of contract workers have the protections they need to feel empowered talking about issues or abuses in their workplaces. When one worker confided in a directly-employed colleague who shared their experience of discrimination in the workplace, the colleague told the worker to not bother taking it to HR—a familiar sentiment to those whose identities have not always been respected in the office culture HR is perceived to protect.

Project Include’s analysis of tech worker experiences during the pandemic illustrates the consequences of worker vulnerability. Just 29% of respondents who identified as contract workers felt they had company support to call out harassment or harm (the same percentage as TechEquity respondents) compared with 55% of directly-employed workers. During the pandemic, 46% of contract workers had difficult conversations with their managers that were poorly handled, compared with 28% of directly-employed workers.

One contract worker explained that because their livelihood depended on the whims and good favor of their manager, they did not feel secure being the one to point out anything from workflow issues to matters of misconduct. Recently, accounts of one worker who tried to discuss and advocate for wage equity, and another who pointed out racial and gender inequities in their team illustrate how the structure of contract work robs people of their voice in the workplace.

Disproportionate Power Leads to Occupational Segregation

Add to this culture the demographic realities that those with workplace power are disproportionately white men, while contract workers are disproportionately Black, Latinx, Indigenous, Asian, women and nonbinary people, and what emerges is an issue of occupational segregation that reinforces harmful gender and racial hierarchies.

Occupational segregation is one basis by which gender and racial pay gaps persist. When certain demographic groups (Black, Latinx, Indigenous, Asian, women, and nonbinary) hold an outsized number of certain types of jobs (tech contract roles), there is a readily available framework by which to pay workers differently while attributing it to different skill or responsibility levels than if all worker groups were equally represented in each field and classification.

Data shows that this is the case even when performing the same functions. That’s why 75% of software developer contract workers who completed TechEquity’s survey are in the the 25th percentile or lower for average earnings. One’s status as a contract worker is used to justify unequal pay for equal work.

Tech diversity is concentrated in the worker groups with the least power.

TechEquity has shown elsewhere in the Contract Worker Disparity Project series that contract workers receive a fraction of the benefits of direct employees. In addition to health care and paid time off, the typical tech benefits package includes stock options. The latest numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that private-sector employers spend about 29.4% of total compensation costs on an employee’s benefits. Put another way, direct employees earn about 30% more than their base pay in various benefits. The total value of higher wages and better benefits make the pay disparities between direct tech employees and contract workers even more severe.

Eroding Labor Practices Lessens Quality of Life for All

Low contract work standards are a piece of how employers are sidestepping their responsibilities, compensation, and job standards for workers around the world. In 2017, workers on Tesla’s production line sought help from the United Auto Workers after years of low pay and unsafe work conditions. One worker revealed that the production team generally earned between $17 and $21 an hour, compared to the $25.58 national average for auto workers and the $28 hourly living wage in Alameda County, where the production line is located.

Increasingly, workers behind tech’s most profitable companies are pushed down the continuum of job quality; they’re downgraded from well-paying full-time jobs with benefits and protections to underpaid and unprotected roles, outsourced either into vulnerable classifications or communities that lack worker protections. Many contract workers report starting out by filling in for a direct employee on some type of extended leave. Eventually, the roles are converted to contract work permanently, allowing the company to save on benefits and termination costs. Today’s covetable six-figure tech job with equity options could be tomorrow’s substandard employment arrangement.

Non-U.S.-based workers who spoke to TechEquity revealed that after having their staffing agency contracts suddenly cut short, they were approached with an opportunity to work for the same U.S. company, doing the same work—but this time as an independent contractor without minimum wage protections, and paying an additional fee to a platform like Upwork that the tech company used to assign work.

The shift from direct employment to third-party contract work, and then to more typical independent contracting or gig work, has a downward effect on worker wages broadly. In Beaten Down, Worked Up, Steven Greenhouse’s book on the history of America’s labor movement, he details how converting what were once full-time, direct employment roles to freelancing affects those still in direct employment, too.

“Many corporations turn to crowdsourcing sites because getting work done through these apps can cost less than half as much as through typical outsourcing, causing a downward pull on workers’ pay, as we’ve seen. For example, to translate a 22-minute video from English to Spanish, a professional translation firm in New York proposed charging $1,500, while on the Upwork platform, five skilled freelance translators from Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, and the Philippines—three of them with five-star ratings—offered to charge just $22 to $33.”

Steven Greenhouse, author of Beaten Down, Worked Up

Additionally, tech employment practices undermine housing stability. One’s ability to secure rental housing depends on the ability to prove steady income. Yet workers interviewed for this project indicated that they most frequently signed employment contracts that ranged from two to six months, contracts that were then verbally extended in repeated one month increments. This makes it extremely difficult to qualify for a home loan or get approved for a rental lease even if, on paper, workers can afford it.

Tech consumers also lose when the sector disempowers workers; homogeneity creates harm. In just a few high-profile examples, facial recognition technologies were trained with overwhelmingly white and male baselines to then create products that automate the eventual incarceration of communities of color, healthcare algorithms have been found to create sicker Black patients than white, and the “tech-ification” of Jim Crow-era housing discrimination led a platform to block people from accessing housing.

Everyone loses when labor practices amplify instability. A recent analysis by HR&A Advisors found that tech was responsible for widening the racial income gap by almost $50 billion. Researchers looked at the gap between Black and Latinx workers and their representation in the industry, as well as the misalignment between worker skill and worker classification to arrive at these figures.

Notably, this study is based on disparities based on race between direct employees, with the total income gap presumably widening when accounting for earnings differences between contract workers and direct employees, especially contract workers with identities at the intersections of multiple forms of oppression. The mounting body of research on contracting in tech has led many to refer to the phenomenon as tech’s caste system. Tech diversity is concentrated in the worker groups with the least power.

The Way Forward

The precedent for modern temp work or contract work emerged in the post-war period, when employers sought an expendable workforce that could fill in personnel gaps without “threatening” the workforce of white men, or the company’s bottom line. In light of the 1999 lawsuit against Microsoft for its illegal use of “permatemps” to avoid paying stock options, health insurance, and retirement benefits, and more recent news about the prevalence of the contingent workforce powering tech profits, it becomes clear that while temp practices did not originate in the sector, they are being applied in tech to incredibly harmful ends in ways that are likely to affect other industries.

To do right by workers and mitigate reputational risk, short of eliminating the two-tiered systems, companies should:

1. Be Transparent about their Workforces

Companies should proactively publish their longform EEO-1 reports. In addition, they should broaden gender data categories to reflect nonbinary and gender-expansive workers, and publish all data on direct workers as well as contract workers.

2. Support the Development of Third Party Reporting Structures

Companies must ensure that contract workers have access to secure systems to report workplace safety and personnel issues that are separate from established HR or management teams. The third-party reporting system must also be responsible for investigating and recommending resolutions to complaints, ensuring those findings are transparent to workers, and HR must partner in an authentic way that ensures real repair to workers who have been found to be harmed. These complaints and their resolutions should be aggregated and disclosed to the board of directors, investors, workers, and ideally publicly.

3. Regularly Audit Contracting Agencies

Tech companies must assess agencies against certain labor and civic values before approving their bids to supply workers to the companies, in addition to regularly auditing those agencies no less than one a year. Companies should require the agencies to submit updated information on their contract workers (that the companies can then publish in their annual workforce data) each audit, including information on their fee rates, worker wages, benefit contributions, [workplace injuries if relevant], and turnover disaggregated by demographic group.

4. Publish Personnel Policies

Tech companies must also make their workforce policies public, including their whistleblower and worker organizing protections, and pay parity policies.

TechEquity’s previous papers provided recommendations on how to change contract work practices to serve workers and companies alike. TechEquity Collaborative continues to work with contract workers and labor partners to develop a comprehensive set of responsible contracting standards and public policy, to be announced later in early 2022.

Project Include will continue to advocate for equitable company practices and policies for all workers that are inclusive and comprehensive, with metrics for accountability.

Tech’s caste system is a vulnerability for the industry, one that needs to change in order to protect workers and ensure that employers fulfill their public commitments.