You’re making AI—whether or not you want to

Renowned Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki isn’t a big fan of AI. When previously presented with an AI-generated animation, Miyazaki had called it an “insult to life itself.”

Nevertheless, in March 2025, people started flooding the Internet with AI-generated images of themselves, their loved ones, and their pets, as well as memes transformed into Miyazaki’s famous hand-drawn art style. Even the White House got in on the trend, using it to illustrate a woman being detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Still, AI in this context might seem innocent enough. An infringement of copyright? The courts are deciding. A perversion of artistic expression? That’s more of a personal judgement.

A product of an extensive supply chain that relies on thousands of poorly compensated workers around the world collecting and labeling data and training algorithms? Most definitely.

Whether or not you took part in the Studio Ghibli trend, you are part of this supply chain as well—from the data on your social media platforms to using AI tools to search the Internet.

Your data

AI systems don’t exist without YOUR data, which is used to train and maintain their models. Luckily for the companies that develop AI, there is an entire industry dedicated to collecting, collating, storing, and selling people’s data.

When we typically think of data collection, many people jump to social media platforms, especially in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

But even if you’re not on social media, you’re likely being tracked online as you surf the web. Whether you’re shopping on or offline, data about you is being compiled. Even your headphones might be collecting data on you.

How do AI companies get their hands on this data?

- They collect data on their platforms, like Google or Facebook, both of which have their own AI systems.

- They purchase data from data brokers or other companies.

- They use web scrapers—sometimes with disastrous, racist consequences.

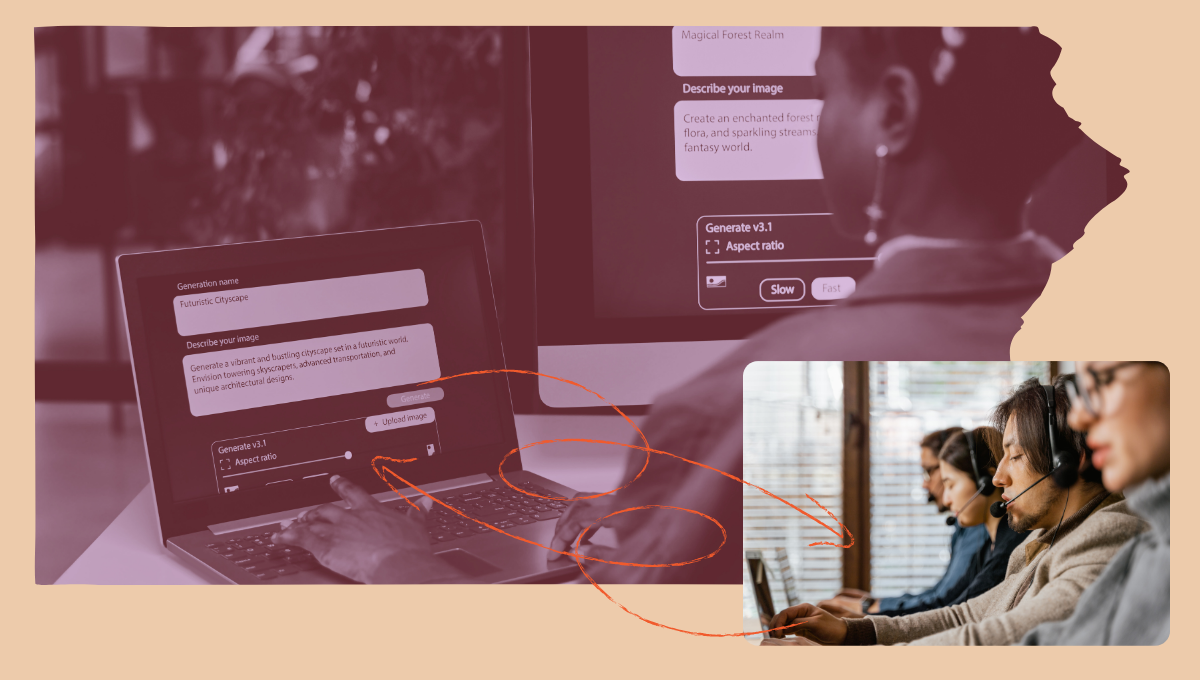

Workers around the world then make this data usable by filtering, organizing, and annotating it. For example, they’ll go through images looking for pictures of dogs, labeling them as such, and putting them all into a data file with other images of dogs. Machine learning is then used to analyze this dataset to identify patterns of what makes a dog. Data workers then reinforce outputs of AI systems by evaluating the results.

Your labor

You likely participate in data labeling and training, too, whenever you run into CAPTCHA tests. These tests were originally meant to filter out spambots, showing users garbled or warped texts that a bot couldn’t read but a human could. You may not have realized that you were actually helping to train machine learning algorithms to identify words through this process. And identifying objects in blurry photos to prove your humanity contributes to increasingly complex and advanced AI systems.

Which, ironically, then helps AI systems get better at pretending to be humans when confronted with CAPTCHA tests.

Another notable example of people unwittingly training AI: Pokémon Go. Users provided location and augmented reality scans even when the app was inactive. Niantic contends that personal information is protected and that users had to consent to data collection when they created a profile on the app.

This example is an important reminder of the adage: if you’re not paying for the product, then you—and maybe your unpaid labor—are the product.

AI developers rely on quality data sets to improve their systems, but much of the work is done by data workers around the world who often report low wages and poor labor conditions. But when AI data sets are developed poorly (perhaps by people who don’t even know they’re developing data sets for AI), the fallout can be highly consequential as AI systems are increasingly used to police people, decide who gets housing, and more.

Your usage

When you use AI, you’re also training AI. Like with any platform or digital tool, there’s the ability for users to report bugs that companies can then fix.

With AI systems, though, users have a more direct (and unknown) impact.

For instance, users may find themselves frustrated trying to find the answer they want from a chatbot. Users might respond with a more specific prompt or a simple “that’s not what I wanted.” In doing so, they teach AI systems to output the right response by giving the system negative or positive feedback.

This is similar to the sort of tasks that data workers perform through processes such as RLHF (reinforcement learning from human feedback), SFT (supervised fine-tuning), and red-teaming.

However, users don’t often know how they’re impacting AI models. They may not realize that buried in an AI company’s terms of service, they may be giving access to “conversations” they thought may have been private—which is especially concerning in the case of AI therapy tools. They don’t know that the photos, works of art, writing, etc., that they input suddenly become property of the company that made the AI. This means that they can also use their data for other use cases, like facial recognition.

Those Studio Ghibli-style, AI-generated images just don’t seem as cute anymore.

Our consequences

In this way, the data in these AI systems can reflect the human biases (racism, homophobia, misogyny, etc.) of other users.

Ideally, these biases would be checked by workers who moderate user impacts on AI models. But these workers are largely overworked and underpaid. For instance, in order to train ChatGPT, OpenAI outsourced labeling of toxic content (hate speech, graphic images, violent videos) to workers in Kenya who were reportedly paid less than $2 per hour.

Thus, workers preventing AI systems from generating harmful content do so at great risk to their own mental health, and things are bound to slip through the cracks.

Without these workers and without guardrails in place around the use of AI, we risk overreliance on tools that could reinforce harmful beliefs even as algorithmic decision-making systems are used to determine access to jobs, housing, and more.

With AI-backed automated decision systems, that’s taken to a whole new level, reinforcing systemic discrimination like anti-Black bias in initial job applicant screenings. So these tools you informed, trained, and used—which are also largely developed by low-wage, poorly treated workers—are then used in ways that harm the public at large.

Not to mention the local and global environmental impact of AI systems.

So, who is really benefiting from this tangled and opaque supply chain? It’s not you. It’s not workers. And it’s not society. Right now, it’s the Big Tech companies that profit

But we’re working to ensure that tech benefits workers and communities as well.

How you can move forward

All of this can feel very overwhelming, especially with the layers of separation between users and workers and Hayao Miyazaki. But all of our fates are intertwined.

You can take steps to protect your personal information and data from AI.

To support data workers directly, you can check out UNI Global’s work towards better working conditions for content moderators and data labelers.

If you want to learn more about legislation mitigating the downstream effects of the current state of our AI supply chain, take a look at our 2025 legislative agenda.

We also have a lot of opportunities coming up to support workers or speak on your experience if you’re a worker in the AI supply chain, so fill out this form to stay tuned!