The Murky Middleman – How Contracting Agencies Profit in Tech

This article is the second in our series on the Contract Worker Disparity Project. Over the next few months, we’ll be sharing our insights and learnings from first-person interviews with contract workers and our industry-wide contract worker survey. To learn more about the project, check out our announcement article and our overview of contract working conditions.

Tech companies famously provide great benefits, handsome salaries, and perks that lead many to regard them as employers of choice. As we highlight through the Contract Worker Disparity Project, these coveted jobs are not the reality for everyone working in tech.

In this article, we’re examining how contracting agencies operate, how they extract profit directly from contract workers, and how the entire system is shrouded in obscurity.

Tech Companies and Contracting Agencies – What you need to know

What is a contracting agency?

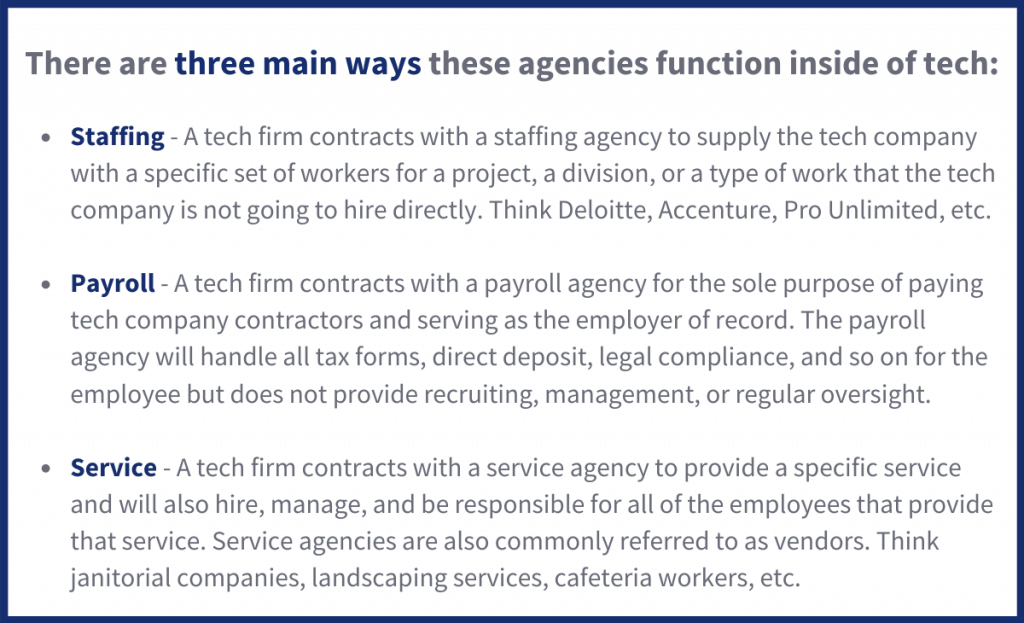

A contracting agency (also commonly referred to as a staffing agency, a vendor, a temp firm, or a payroll agency) is an entity that hires workers for the purpose of supplying labor to an outside company. We are examining this practice as it applies to the tech industry, but the staffing agency model is common across industries.

Why do contracting agencies exist?

Contracting agencies have become deeply embedded in the American economy over the last several decades. According to the American Staffing Association, there are 25,000 contracting agencies in the U.S.—but this trend is not new. The practice of shifting portions of the labor force from direct employment to the payrolls of contracting agencies became prevalent after World War II. The staffing industry billed itself as being able to fulfill flexible, temporary roles with “ideal” employees—without the long-term commitment to an individual worker of a family-sustaining income, benefits, or retirement.

Contracting agencies (and what is often called temporary work) got momentum and took off during the mid-twentieth century with the concept of a “Kelly Girl,” a housewife with “extra time on her hands” who was looking for a foothold into the labor market when direct employment was reserved for white men. With the Kelly Girl, job seekers likely to face discrimination in the workforce at large found a modicum of stability in substandard employment arrangements, and the modern contract work model (and its embedded inequity) was born.

Why do tech companies use contracting agencies?

Different companies—and even departments or teams within each company—provide different reasons for using contracting agencies to bring on workers. Here are the most common we’ve found:

- Streamlined hiring processes – At most large companies, adding full time, direct employees requires multiple levels of sign-off, budgetary allocations, and often numerous reviews and presentations. For many teams, it is much simpler (fewer necessary approvals) to use their discretionary or general budget to hire with a contracting agency to increase the number of workers on a project or team quickly.

- Flexible capacity for temporary needs – companies might choose to use a contracting agency to cover for direct employees who are on leave, or for temporary projects or ones that do not have long-term funding.

- Securing services that aren’t core to the business– Companies often hire out services—like catering, facilities operations, or similar—that are ancillary to the business and that other firms have greater expertise to provide.

The tech company saves on the cost of benefits by using an agency, but more so than cost savings the real motivation for the company appears to be flexibility. A February 2021 study from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (“BLS”) found that labor trends in temporary help services, under which contract workers fall per BLS definitions, predict employment trends in the larger economy.

“When the economy expands, employers are able to ramp up quickly by using temporary workers until permanent staff are hired. Also, temporary help agencies offer flexible staffing, candidate screening, and the opportunity to try out potential hires before committing to a permanent employment contract. Conversely, when the economy contracts, flexible labor arrangements provided by temp agencies allow firms to scale down their operations readily and without the added expense of separation pay or having to let go of their best workers.”

When departmental budgets look uncertain or suddenly shrink, there is a class of workers, never fully integrated into the larger office culture, who can easily be let go tomorrow.

Some of the workers interviewed for this project are eager to find a different, direct-employment job at the end of their contracts, while others work for two years until they’re commonly compelled to take a six-month break (an effort to skirt employment law standards that could reclassify contract workers as direct employees) before signing a new contract. Regardless of their choice, many workers report that the contracting agencies consistently reach out to them about new opportunities in the same or similar roles, belying the claim that contractors merely perform temporary or ancillary business functions.

Turning a Profit at a Cost to Workers: The Knowns and Unknowns of the Contracting Agency Model

Demand is up and rising for contract agency services, but that doesn’t equate to an increase in wages for contract workers. The model is murky, where tech companies are often signing contracts with the lowest bidder without much insight into how the agencies achieve their price point. But capturing the true impact on wages, job security, and professional experience for the contract workers is nearly impossible. Lack of data reporting, standardization, and accessibility about worker experience has created a stratified and invisible class of workers within tech companies. In this section we explore the depth of those imbalances.

Increased Demand for Contracting Agencies; Falling Wages for Workers

The simple narrative that contract work saves money—rather than shifts who pays the costs— obscures the profit that contracting agencies generate from the model. The initial pitch in the post-war workforce trumpeted cost savings—by offering lower wages than those of direct workers and foregoing benefits, onboarding, and recruiting costs, the company can improve its bottom line. Research on today’s contract work environment indicates that tech companies often pay contracting agencies enough for them to offer family-supporting wages, but to ensure their profit margin, the agency eats into workers’ earnings.

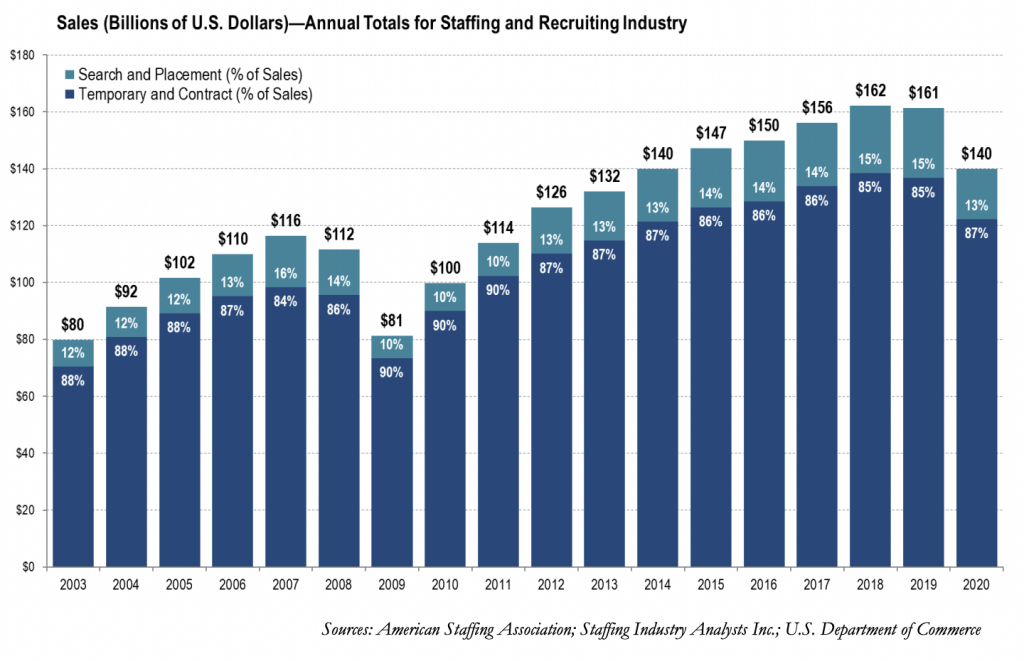

BLS data on temporary help services, or supplemental workforce, suggests that demand for contract work in skilled industries is increasing, and becoming more profitable for the contracting agencies.

The latest numbers from the American Staffing Association show the coronavirus pandemic modestly affected contracting agency revenue compared to the nearly record high of $160 billion in 2019. Still, 2020 ended at $140 billion in revenue for the contracting industry, marking a 175% increase over the past two decades. There is a similar dip and rebound around the 2008 recession; despite market uncertainty, demand for contracting agencies has consistently increased. However, increasing revenue for staffing agencies does not translate into more income for contract workers.

A 2008 study by BLS economists found that in the period from 1990-2008, employment in temporary help services doubled, particularly in highly-skilled industries including tech. Conversely, as staffing agency employment doubled, worker wages decreased. Staffing agency contracting for computer and mathematical roles—just one of the types of roles that contract workers in tech fill—increased 41% from 2004-2008 alone while wages decreased 7.4%.

Lack of Transparent and Accessible Data Leads to an Ever-Invisible Workforce

While we know that the contract workforce is increasing, sussing out the true disparities in worker wages and the profit margins they yield is inexact in the tech industry. Drawing similarities for pay parity is reliant on patchwork, imprecise, and non-parallel job categorization. This means there is no comprehensive view of tech as an industry. Staffing and temp agencies report the job categories (e.g. office and administrative support, construction, etc.) of the employees they place, not the industries in which they place them.

Of the hundreds of workers who have submitted information for the Contract Worker Disparity Project, over 20% have said they work in job categories outside of our thirteen-category list. Within that 20%, few submitted duplicate responses, pointing to the sprawling and sometimes disparate job categories across the contract workforce. Because BLS tracks what contract workers do— not necessarily the employer or industry for which they do it—people who work on contract in operations, marketing, administrative services, etc. within tech are invisible in the data. The lack of data also conceals just how many tech companies rely on agencies for their workforce.

Profit Margins and Markups on Labor Drive Murky Decision-Making

The tech companies are in the dark, too. They mandate the number of people the agency must hire, and the total contract amount but most don’t set a wage rate within the contract—either for the contract workers or the staffing agency workers whose earnings also come out of the same funding.

TechEquity has confirmed that agencies often take upward of 30% of the money they receive from the tech company in recruiting and contracting fees. Across the contracting industry, mark ups can be as high as 100% of a contract worker’s wages. Conversations with contract workers, contracting agency staff, and direct tech employees indicate that the agencies pocket between 20—50% of the total contract amounts, but the vast number of agencies and roles suggests there is even more variation in how much the agencies profit.

Tech’s Internal Processes Perpetuate Poor Contracting Practices

Bringing in the lowest bidder can often mean cutting corners — to the detriment of contract workers. We reviewed a number of tech companies’ Request for Proposals for labor contracts to understand how they make decisions in the contracting process. Here’s what we learned:

As mentioned above, many team leads and contracting managers have an incentive to bring in workers faster and under non-committal terms.

When hiring managers decide to use contract workers, most write a proposal that goes to their procurement team. That team is responsible for selecting the contracting agencies and the terms of their service. A number of the conditions that contract workers will experience are set from the outset by the procurement process.

Those processes award funding to the “most competitive” bid—a practice that typically rewards proposals that offer to deliver a labor pool for the least amount of money, resulting in a race to the bottom on cost rather than equitable outcomes for its workforce. While the total amount can look sufficient enough to give workers family supporting incomes, the cut that contracting agencies take out to cover their own costs and profits brings workers’ earnings down.

With over 25,000 staffing agencies, tech procurement teams often decide who to contract with based on who can get the job done the fastest for the least amount of money. Proposals that cut corners in order to give tech the best deal possible are more competitive. Procurement practices that emphasize cost containment above all else send a clear message to contracting agencies that their priority is affordability, not quality of employment.

A TechEquity review of tech contracting Requests for Proposals (“RFPs”) found solicitations that emphasize cost-competitiveness and high-caliber employees willing to go above and beyond to provide a great service. Those requests did not in turn ask contracting agencies to submit their wage standards, overtime rates and process, benefits packages, turnover rates, management evaluation and training process, or other details that would indicate a contracting agency’s ability to hire, cultivate, and retain a first-class workforce. When costs are “cut,” they are in reality borne by the workers, in the form of reduced wages and/or limited access to healthcare, childcare and other necessities.

What This Means for Workers

Contract workers enter their roles with even less visibility into the contractual relationship between contracting agencies and tech companies. This model makes it difficult for workers to advocate for themselves which puts them at additional risk for exploitation.

The lack of transparency about where the money is and who really directs it adds an additional frustration (on top of the precarity of contract roles) to advocating for better job stability and protections. A staffing agency for Facebook recently claimed that Facebook mandated cut backs in paid holidays for janitorial contract workers. After questions arose about whether Facebook had really ordered the reduction (it released a statement saying it hadn’t) or if it was the contracting agency trying to pocket more of their contract, the agency reversed its decision—after six months and four working holidays had already passed.

Staffing agencies recruit and vet candidates, while contract workers who are hired because of an internal referral by a direct employee at the tech company frequently sign a contract with a payroll agency, who don’t recruit employees but act as their official employer. Because they aren’t recruiting or screening candidates, payroll agencies (one type of contracting agency) typically take less of the overall contract than staffing agencies (another, more common, type) because their costs are lower. Payroll agencies are able to redirect the savings into contract workers’ earnings.

Many workers aren’t aware of the distinction between the two types of contracting agencies or what it means for take home pay. TechEquity spoke with someone involved in securing contract workers for a large tech company who expressed dismay that good workers were at an earning disadvantage simply because of whether or not they knew someone who got them the job. In practice, this means that workers who come in via referral tend to earn higher wages than those who don’t already have a professional network that reaches into the tech company—a model that exacerbates the homogenous demographics of those who have the opportunity to advance in tech.

The contracting agency model can exploit workers even when the tech company intervenes. One worker who spoke to TechEquity reported that their tech company offered them a $10-an-hour raise. Soon after, the worker’s contracting agency let them know there was an issue implementing the raise because doing so would mean the money would come out of the earnings of staff at the contracting agency. It took several weeks for the tech company manager and contracting agency to iron it out; when they did, it didn’t include back pay for the delay period.

It is rare that the contracting agencies specialize in tech placements exclusively. Often, they place workers into a range of jobs and industries— a diversification that lessens the quality of support and feedback they are able to provide individual contract workers.

The contract workers who have spoken to TechEquity consistently report low-quality relationships with their contracting agencies. Some struggled to remember the names of their agencies, having to consult their pay stubs to jog their memories. Others shared that they didn’t hear from the agency for the duration of their contracts after they signed. The colleagues that share daily experiences and struggles work in teams alongside each other, but may be employed by different agencies and receive different levels of employer support, making it hard for workers to band together to advocate for themselves.

What This Means for Tech

Tech companies have a natural incentive to advocate for and enforce better contract worker practices. The risks are many: litigation (joint-employment standard and co-employment generally arises from mistreated workers, inequitable pay and benefits, and substandard working conditions), fiduciary responsibility to mitigate the profit loss that results from misclassifying workers, the reputational risk, not to mention that attracting and retaining talent is one of the core drivers and predictors of business success.

Reputational Risk

For the tech companies, the proliferation of second-rate employment, without regular reporting from the contracting agencies, presents risks. Low worker morale is bad business. In recent years, contract workers have sued, walked out, and organized over their treatment, pulling companies into the spotlight and questioning their reputations as great places to work.

Beyond public relations considerations, current contract worker practices are a drain on productivity, and ultimately tech’s bottom line. Report after report finds that happy workers are better workers, with some research finding them to be 31% more productive and 19% more accurate on task completion.

Legal Risk

Moreover, the demographic differences between contract workers and direct employees, as well as the pay and demographic disparities between payroll agency contract workers and staffing agency contract workers, could invite disparate impact and other legal scrutiny. The disparate impact legal standard holds that employers are responsible for practices that create different outcomes for groups based on their race, color, religion, sex, or national origin even if those practices are applied neutrally, or irrespective of those characteristics. There could be issues of employment discrimination if hiring practices result in discriminatory outcomes, including workers with protected class status disproportionately assigned to lower paid roles.

Opportunities To Even the Playing Field

Fortunately for tech, other industries can offer a roadmap for how to do better. Organized labor advanced the concept of prevailing wage in the late nineteenth century, with Congress ultimately passing the Davis-Bacon Act in 1931 to govern minimum pay and benefits standards for federal contractors. Since then, governments have expanded high-road standards for contractors to include not just pay and benefits, but to advance certain principled outcomes including sustainable business practices, businesses owned by disabled veterans and more. Bidders are then assessed by their qualifications to meet those standards in addition to their cost competitiveness.

Tech Companies Can (and Should) Require Contract Standards

New commitments from Google and SurveyMonkey illustrate what’s possible when tech companies require that contracting agencies adopt certain improvements as requisite to earning a contract. Contracting agencies are unlikely to offer better conditions to employees unprompted if it cuts into their core business model when they’ve found a way to extract profit off of the lowest possible bid to a tech company. While minimum standards are a necessary first step, problems persist; future efforts to remedy issues in the contract workforce must also address the precarity of contract workers’ roles and the exclusionary office culture they often face.

Tech can follow in the public sector’s nearly century-long lead of ethical procurement practices that favor not just low cost bids, but ones that help client companies be good civic partners. Reorienting procurement teams to focus on bids that promise family-sustaining pay and benefits as well as employee support is a critical step to bring tech into alignment with other industries.

Improve Transparency in the Contracting Model

Efforts to realize better conditions for contract workers must be paired with more transparency and disclosure. At each stage in the process, from the time the contract is developed to the time the contract worker leaves the company, disparities worsen because information is withheld. Procurement teams withhold who submitted bids to the Request For Proposals and why the successful bidder was ultimately chosen. Contracting agencies withhold how much of the contract they take for internal services, and how those costs are distributed. Both withhold information about the scale of the practice and who the workers are.

When the lack of transparency persists, the exploitative labor model of tech contracting does too, and contracting agencies are left to pocket the money that contract workers should be earning. Tech companies and contracting agencies alike should publish disaggregated data that enables informed analysis of the contract workforce. Tech companies must report a list of the vendors and agencies with which they work, as well as aggregate data on employees including racial, gender, and pay demographics in addition to years with the company and classification.

BLS data on temporary help services should include the job category as well as industry. A complaint platform housed at BLS or another centralized source would allow tech companies to learn about agencies with poor labor records before accepting their bids.

Lastly, workers should be able to—and have— create informal networks to share information and organize. The platform on Coworker.org has helped workers run campaigns to improve their working conditions. Advocacy that makes direct employees allies in the fight for fair treatment has produced results. The Alphabet Workers Union is one clear example of how contractors and direct tech employees can organize together. When companies return to in-person work, opportunities like Employee Resource Group meetings are another promising venue to educate direct employees about the disparities of contract work. In a system that incentivizes a two-tiered caste system amongst colleagues, worker solidarity is a threat.