Why is the rent so damn high?

Last week we hosted a panel to answer the question: why is it so expensive to build a unit of housing in the Bay Area? It’s a surprisingly complicated question, but the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC-Berkeley has been doing really great work trying to get to the bottom of it.

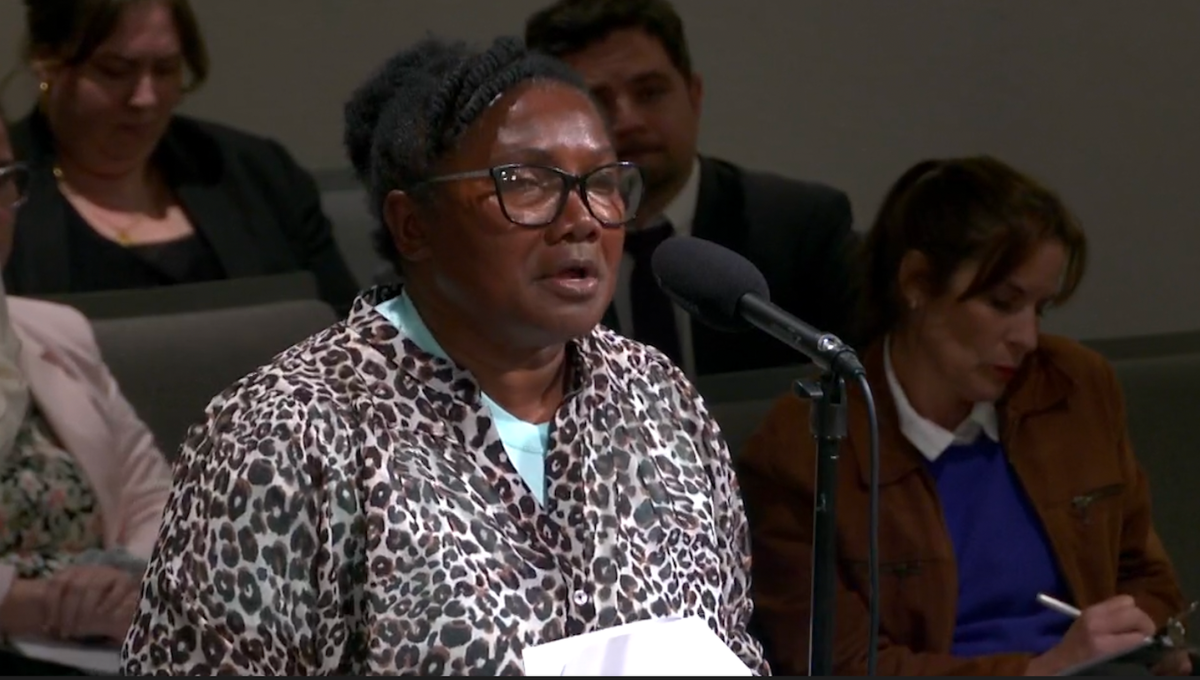

We kicked off the evening with Elizabeth Kneebone, the Terner Center’s Research Director, presenting the Center’s research on the topic. You can find more about the research here and the slides from the presentation here. Some key takeaways from what is a really rich, and still ongoing, set of work:

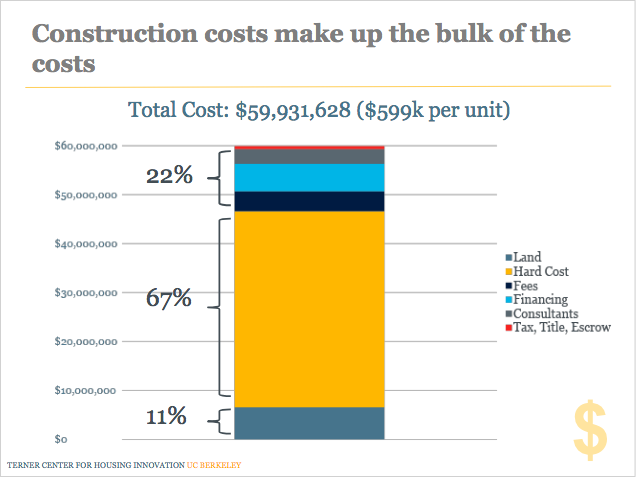

- An optimistic estimate for what one apartment unit costs to build in the East Bay is about $600,000. It’s likely higher in San Francisco. The team is still doing research to see how this compares to the rest of the country but everyone suspects it’s significantly higher than the national average.

- The answer to the question “why does housing cost so much to build?” is: It’s complicated. Elizabeth used the term “death by a thousand cuts.” All of the various costs (see the chart) add up to create the high cost of development. This layering of costs can make it tricky to determine where to focus efforts on reducing costs.

- While hard costs (mostly labor and materials) make up the lion’s share of the total cost, about 67%, it’s not entirely clear what elements within that category are driving increasing cost. The Terner Center is continuing their data gathering to illuminate the answer.

- There are real tradeoffs in thinking about where and how we reduce the cost of development. Many fees and regulatory requirements, which add costs and make it harder to build, are in place for good reasons. Finding the right balance between regulation and cost is a complicated task.

After Elizabeth presented Terner’s research, we had a great conversation with a fantastic panel about various aspects of high development costs and the realities of housing finance. We were joined by:

- Andrew Cussen of RAD Urban. RAD Urban is one of a few developers innovating on the process of manufacturing, doing most of their building in a factory rather than on a job site. Apartments are built like giant lego sets and shipped to the site to be assembled there. Working this way creates significant efficiencies which can decrease the cost of a development project by as much as 20–25%. Andrew talked about the challenges of bringing this kind of manufacturing to scale, which hinges a lot on the willingness of the building trades and laborers to work in a new and different way. That cultural change can be really hard.

- Rich Gross of Enterprise Community Partners. Enterprise does all kinds of work in the affordable housing space, including providing financing for affordable housing projects. Rich helped us understand the financial realities of getting projects built, which I outline in a bit more detail below.

- Linda Mandolini of Eden Housing. Linda outlined the unique challenges facing affordable housing developers. They will never qualify for the kind of financing private developers receive because the people they rent to will never be able to afford the rents that would pay those investors’ returns*. And the public sources of capital available to affordable housing developers come with many more strings attached, which causes the cost of building to go up. In addition, sources of capital for affordable housing developers have been scarce for decades and are not close to keeping up with demand.

Financial Realities

The panelists helped us understand how financing for housing works, and how it creates the conditions where the consumer cost of housing is so high. Private developers must find funding from large-scale financial institutions, like banks and equity investors, in order to make projects viable. To secure that funding, developers must be able to show that the projects will produce a return — according to Andrew it’s about 16% — over the course of the investment. This means that if the cost of developing a unit of housing is high, the costs that must be passed on to the renter or owner in order for the developer to secure funding must also be high. That’s why we see a saturation of high-end market-rate housing — because those are the only projects that can get financed.

There was some discussion about encouraging more investors to settle for lower returns in order to reduce the price of the units on the rental market, and Rich gave a few examples of investors who are open to this, but it’s not the norm in the private market. Ultimately, if the private market is going to serve more people at lower price points, we will need to find ways to bring the cost to develop a unit of housing down.

Financing for affordable housing is another story. The capital to subsidize development can come from a variety of sources but the biggest source of capital for these projects is through a federal tax credit program called the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) where corporations can buy tax credits from nonprofit developers in order to save on their tax bills. The nonprofit developers then use that revenue as capital for development costs. That program is limited though, and doesn’t provide enough capital to meet the need. In the wake of the federal tax reform legislation, these tax credits have also become less attractive to corporations as they have less of an incentive to need to reduce their tax burden.

Other funding can come from state and local governments, and if you’ve voted yes on a bond measure for housing in the last few years you’ve helped to contribute to that capital pool. However those bonds are one-time-only funds — they are not sustainable and replenishing sources of funding for ongoing development. Also, as I mentioned, the capital needs of affordable housing developers are higher because added regulatory burdens drive up the cost of building. This means that money doesn’t go that far in a world where one unit costs $600,000, conservatively, to build.

This is all a long way of saying: we have a real challenge in front of us if we are going to meet the dire need for low- and middle-income housing.

How do we fix this?

Much of the conversation revolved around solutions: what opportunities exist to cut a little bit here and a little bit there to bring the cost down enough that the market can serve more people? And how do we find more sources of capital for affordable projects that would never be viable on the private market?

Prop 13 reform. It wouldn’t be a TechEquity event on housing if we didn’t touch on Prop 13, California’s regressive property tax law that pegs taxes paid to the value of the property when it was purchased — even if it is much more valuable now. It was passed as in 1978 as a way to protect people on fixed incomes from losing their homes because they can’t afford property taxes but it also covered commercial and industrial properties in addition to residential ones. Property taxes are the main way local governments pay for services, and the inability of local governments to increase revenue from this source not only starves municipalities it creates conditions that contribute to the high cost of housing:

- Because cities can’t extract more taxes over time from residential property, they load up the projects with fees at the outset which drives up development costs

- Because land owners don’t have increasing property tax bills, they don’t have incentives to sell their land which drives up the cost of land

- Much of the funding that is lost to Prop 13 (an estimated $10b per year just from commercial and industrial properties) could be allocated to affordable housing development and would obviate the need for constant bond measures.

TechEquity is playing a leading role in the Schools and Communities First Campaign, to pass a statewide ballot initiative that would close the commercial and industrial loophole in Prop 13 and restore that $10b in annual funding to local governments. It will be on the 2020 ballot.

Funding Streams for affordable housing. As I hope we’ve made clear, the funding situation for affordable housing development is dire. We have to find new sustainable revenue sources for affordable housing developers. At the federal level, we could expand the LIHTC and find ways to make it more attractive to corporations. We could also establish new revenue streams for affordable housing development. However, change at the federal level seems particularly unlikely under the current administration.

One promising option at the state level (aside from reforming Prop 13) is to bring back redevelopment agencies. Redevelopment agencies, which provided dedicated funding for low-income housing development among other things, were eliminated by Governor Brown in 2012. David Chiu has introduced a bill to bring them back, which also addresses some of the reasons they were eliminated in the first place, but the bill has stalled in the legislature this year. There is some promise it might gain more traction next year — Gavin Newsom, who is likely to be California’s next governor, has expressed support for reinstituting the agencies.

Subsidies for prefab manufacturers. Much as government has subsidized other industries it had an interest in seeing grow (clean energy for example), we could provide government investment for the prefab manufacturing industry (companies like RAD Urban) so that the sector can scale. Without massive scale the cost savings we can achieve through innovations in the manufacturing process are unlikely to be reflected in the consumer price of housing.

We’ll have a new governor next year, who will enter office with housing as a top priority. He is also likely to be friendlier to affordable housing than the current administration. This means we have a window of opportunity to push an agenda that attacks these costs centers and provides much more sustainable funding sources for affordable housing. We will be on the front lines of pushing that policy agenda in the new year.

*Affordable housing is typically housing that is subsidized in some way in order for it to be affordable to people making 30 to as much as 110 percent of area median income (for reference, the area median income in San Francisco for a family of four is almost $120,000/year).