The Promises and Perils of Residential Proptech: In a Nutshell

Whether you are trying to find an affordable apartment or buy or sell a home, technology is behind an increasing number of today’s housing decisions. As the “Residential Proptech” sector, as it is known, grows, it has promised to dramatically decrease the cost of producing new housing, expand ownership opportunities to marginalized communities, and streamline the tenant/landlord relationship.

According to its proponents, Residential Proptech will make housing more accessible and affordable, and eliminate much of the discrimination embedded in America’s housing system. But Residential Proptech also has the potential to exacerbate the bias inherent in our housing system.

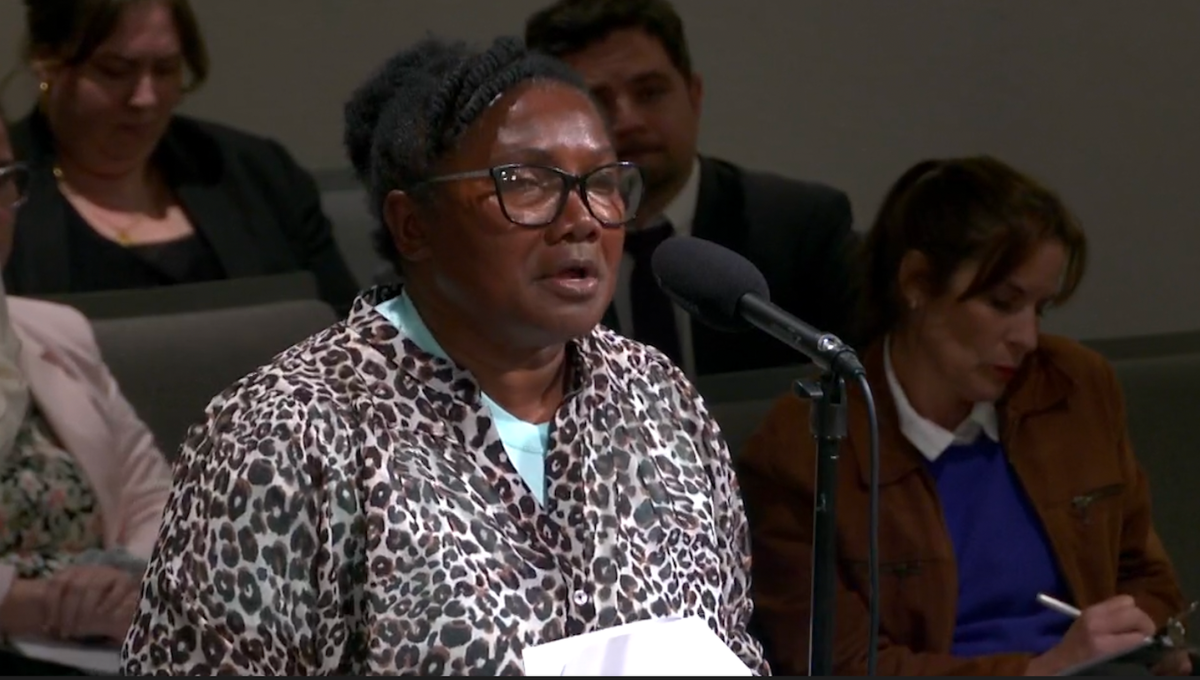

For the past year, we’ve been researching property tech’s impact on housing as part of our Tech, Bias, and Housing Initiative. You can download the full report below, or keep reading for a brief summary of our findings.

THE PROMISES AND PERILS OF RESIDENTIAL PROPTECH

Download the research summary report here

To understand the risks, as well as the potential benefits of Proptech, it helps to revisit how we got here.

1. Landlord Tech Enables the Financialization of the Housing Market

In the wake of the devastation of the Great Recession, Wall Street saw an opportunity in the single-family housing market. In 2008, U.S. foreclosure filings spiked by more than 81%. With so many homes newly unoccupied and too few people with homebuying resources, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) created the REO (Real Estate Owned)-to-Rental program in 2012—a pilot program that paved the way for large investors to purchase foreclosed homes in bulk and turn them into rental properties. The program’s intent was to prevent vacant homes and communities; it did so by bringing the profit motives of private equity firms to America’s doorstep.

With new digital tools and thousands of data points, investor owners came to use algorithms to optimize for profit—at the tenants’ expense.

As this landlord tech, as it would become known, took hold, more property managers of all sizes came to rely on it to interface with tenants. One key feature of landlord tech is the use of algorithms to screen rental applicants and assess their suitability as tenants.

Before the advent of algorithmic tenant screening, landlords vetted tenants by having them submit their own records and references from previous landlords or others who could vouch for their trustworthiness. Algorithm-backed screening services, on the other hand, are bundling all the traditional information (whether accurate or not) alongside predictive models. These predictive models make guesses about whether an applicant will be a responsible tenant based not on the history of that specific applicant, but on (as far as we can tell) behavior trends of applicants who have similar characteristics. The data behind these models is rarely made available to either the tenant or the landlord.

From information on company websites, it is not clear what analysis or data is behind subjective determinations of tenant suitability. Based on sample reports, even landlords are not privy to how the determinations are made. Instead, they receive a risk score out of 100 simplified into green, yellow, and red recommendations.

The emergence of synthesized risk scores using predictive models raises questions: do existing consumer protections such as the Fair Credit Reporting Act apply? Are the landlords that use these services receiving the information they need to fulfill their obligations under the Fair Housing Act?

2. Emerging Alternative Financing Options Reflect Some Predatory Characteristics of Past Models

The expansion of the pool of people left out of the traditional mortgage market, along with a constriction of housing supply and increased competition from investor buyers, created a market for startups offering alternative pathways into homeownership. Of the many models that purport to make homeownership accessible through something other than a traditional mortgage, Rent-to-Own (RTO) has so far gained the most traction.

RTO companies purchase homes on behalf of buyers and retain that ownership until the buyers have made consistent payments over a period of years. These companies can play an important role in easing the path to homeownership for families that would not yet qualify for a traditional mortgage. However, RTO bears some similarities to a Jim Crow housing practice known as Contract-for-Deed (CFD).

TechEquity’s comparison of modern RTO models found that many do improve on traditional CFDs with clear terms, future option prices (the pre-agreed price that a buyer will pay for the home), and connection to homeownership counseling. However, some important elements of the arrangements, such as how maintenance is handled and how an option price may change in a shifting market, leave room for buyers to be exploited.

3. Venture Capital Fuels Rapid Expansion with Unclear Housing Outcomes

The rise of Proptech is due, in part, to the desperation felt by average home seekers. As unprecedented capital investment flows into this space, venture-backed companies’ winner-take-all approach to growth has the potential to exacerbate inequality rather than combat it.

Because of a lack of transparency in the market, we don’t have a clear understanding of the demographics of the companies’ target markets. We do know that they heavily concentrate in lower-middle-class neighborhoods and communities of color. Many Proptech companies advertise to people who want to purchase a home but whose credit scores suggest they have “hit a few bumps in the road,” or to tenants that might not have enough cash on hand to pay a security deposit in full. This marketing is powerful, bringing in customers who are hoping to find stable housing despite their income restraints, but who end up paying more for it in the long run.

4. Expanded Rights, Protections, and Transparency Offer a Way Forward

As we enter this new era of America’s housing history, we must ensure that practices of the past are not transmuted into new tools and business models that have the power to amplify the exclusion that persists in our housing system.

To get us on the right path, we need to both double down on the policies we know work, like building new housing and strengthening tenant protections. We also need to adopt new policies that target the role of technology and new venture-backed business models directly. We encourage Proptech companies to adopt industry standards that will prevent harm and invest in the ways that technology can help make housing’s future more equitable than its past.

Want to share this summary? You can download the executive summary here: