Venture capital, explained

The modern tech-driven economy is not working for most of us.

Landlords are increasingly using AI-backed technology with baked-in bias to decide who they rent to. Many governments are using untested tech to determine who gets benefits like unemployment and food stamps. Some companies use tech to choose who gets an interview for a job.

But the technology doesn’t appear out of thin air. Technology—and how it’s used—is developed through defined stages full of people making decisions to optimize for usefulness, impact, and (usually) above all, profit.

Each of these stages is typically funded by venture capital. To put it simply: in order to sufficiently address tech’s inequities, we need to follow the money.

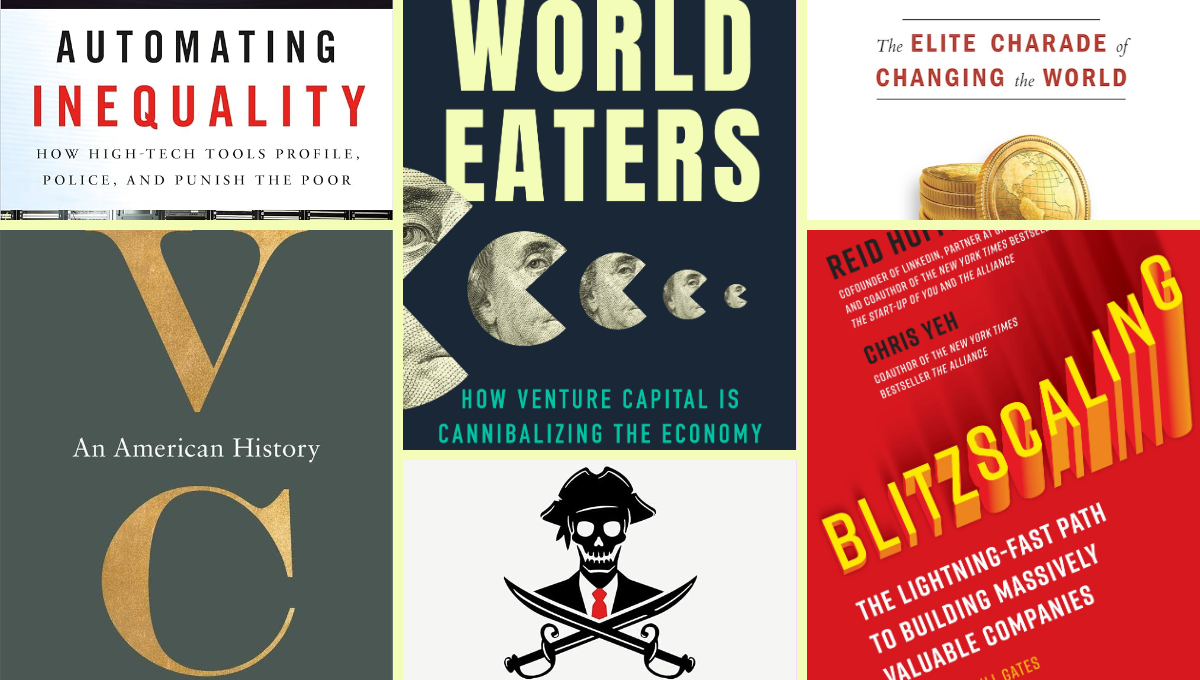

That’s why TechEquity Founder and CEO Catherine Bracy spent the past three years researching venture capital and writing World Eaters: How Venture Capital is Cannibalizing the Economy.

But what is venture capital anyway?

What is venture capital?

Venture capital (or VC) is capital invested in a project with a substantial element of risk, typically a new or expanding business. VC investments can come from an individual funder but typically are arranged by a VC firm investing the money of multiple investors in multiple early-stage companies.

Venture capitalists invest in a company in exchange for equity—a portion of the value of a business. The value of a business is calculated by subtracting a company’s liabilities (such as debt) from its assets (what it owns).

This is different from trading on the stock market, as VC is a type of private equity. Private equity is a type of private financing, aka investing in a company that is not publicly traded. Companies determine who their stockholders are rather than opening up their investments to the public.

Why does venture capital exist?

Silicon Valley, which prides itself on developing ground-breaking technology, is chock-full of venture capitalists and VC firms. Venture capitalists were crucial in nurturing the early computer industry, investments from which many have benefited.

But the concept of VC has its origins in a much older industry: whaling. Like the tech industry, whaling was a highly lucrative but risky industry that demanded investments up-front with no guarantees—many boats got lost at sea. But if even one boat returned with a bounty of blubber, it would more than offset all the other losses.

VC today is still about financing the search for that “white whale”: the high-risk, early-stage ventures that could produce groundbreaking technology—and the dividends that come with it. The US government started de-regulating and lowering taxes for the investment sector in the 1970s to promote bold investing in the name of technological progress and economic growth.

Tech founders reach for VC because most banks aren’t in the business of high-risk investments. Other types of private equity usually deal in companies that are further along in their development or involve purchasing some assets like real estate. There are also angel investors: high-net-worth individuals less focused on achieving significant financial returns and more driven by the satisfaction of nurturing a new company—a financial fairy godparent of sorts.

But the vast majority of growing startups don’t get the fairytale treatment. They have to constantly hustle for VC money to sustain themselves in the early days, hoping that they can make it to the black before they go bankrupt.

How does venture capital work?

It’s not easy to get VC money nowadays—even if you have a great idea.

First, founders need to have and develop an idea. This is known as the pre-seed stage in which venture capitalists are unlikely to invest, so founders need to rely on their own resources and contacts. Founders may participate in a business incubator to get additional resources.

In the tech industry, these incubators are often startup or seed accelerators: fixed-term, cohort-based programs that include mentorship and an educational component. Startup accelerators are closely aligned with VC and some even double as VC firms, like the famous Y Combinator. These programs are seen as a golden ticket for startups to get to the seed stage of funding.

At the seed stage, founders are trying to prove that they can grow and scale their business to VC firms or individual investors to get the funding they need to actualize their plans.

The work is still not done after securing that funding. Next is the Series A stage—raising more capital, honing in on the product and customer base, and generating a plan for long-term profits. There’s then the Series B stage of funding when a company is ready to scale and prove performance—and hopefully get more VC money. Finally, there’s the Series C stage. If a company makes it here, venture capitalists are usually champing at the bit for a piece of the pie.

The name of the game is to move through these stages, scale up, and create large returns as fast as possible, whatever the cost—and we’re not just talking financial. Also known as blitzscaling, the idea is to accelerate at a speed that knocks your competition out of the water so that whether or not you have a superior product or even make a profit, you ultimately corner the market.

Most companies aren’t able to fit this model and will fail as they try to shoehorn themselves into it. Venture capitalists know this. They’re not concerned, though, as they’re operating under the power law: firms only need a small number of successful investments to generate the vast majority of returns.

Instead of using this concept to back truly breakthrough “white whale” technology, many venture capitalists today are just trying to reverse-engineer the successes of the past in the quest for wealth.

How does VC drive the harms that the tech industry creates?

Because of this, recklessness—around the impacts on your workers, consumers, and the public at large—in the quest for maximizing profits is rewarded.

When companies try to scale up rapidly, 8-hour workdays are insufficient. When trying to cut costs to capture markets and get big financial returns, giving workers benefits like healthcare is inconvenient. Companies often outsource to third-party contracting agencies in the name of agility, which can lead to exploitative conditions for these workers.

The gig economy and contract work have been means by which companies can classify workers vital to their growth as contractors for whom they aren’t liable.

As for the products, venture-backed companies are incentivized to put them out on the market as soon as possible, whether or not the product has potential adverse impacts—or even works. Market size is also key to venture capital; indicating the potential for significant growth and revenue generation. There is no bigger (and consequential) opportunity than the $45 trillion American residential real estate market.

The result is Proptech—promising to dramatically decrease the cost of producing new housing, expand ownership opportunities to marginalized communities, and streamline the tenant/landlord relationship.

But with little regulation and transparency alongside the pressures of venture capital, leaders at Proptech companies are disincentivized from making sure that their products don’t perpetuate bias. In the cases of alternative home financing and rent-setting software, they can even be incentivized to participate in or enable predatory practices.

Marketing your product as revolutionary becomes more important than creating a revolutionary product. That’s how you get high valuations and high returns for investors based on speculation. That’s also how you get scammers like Elizabeth Holmes.

Want to get a deeper understanding of VC?

Venture capital was supposed to be about funding the future. But instead, we’re finding our futures bought and sold in the name of a few getting rich.

This isn’t where the story has to end, though. Through economic reforms, worker protections, and other regulations, venture capital can become what it was supposed to be—a vehicle to give life-changing, sustainable products and services a chance.

If you’d like to learn more, check out our Founder and CEO Catherine Bracy’s forthcoming book World Eaters: How Venture Capital is Cannibalizing the Economy.